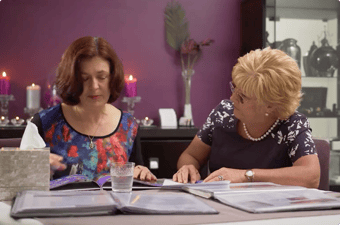

The first time it happened I couldn’t believe it. I was watching a GP hand a grieving family their loved one’s death certificate…in a carpark. Instead of visiting them at their home — instead of showing respect for his deceased patient — he was meeting them in the carpark of his practice. He signed the death and cremation certificates, and, with barely a word, was gone. I was instantly saddened by what looked to be nothing more than a transaction.

Unfortunately, as a funeral director I know that this exact scene happens far more frequently than it should. It's not only impacted patients and their families, but the general quality of GP support in nursing homes. When you consider that around 170,000 elderly Australians are currently living in aged care (a figure that’s not expected to drop any time soon), it’s more critical than ever that we address issues surrounding duty of care...and start providing the support that patients deserve.

Processing the news of a loved one’s death is already a whirlwind of emotion and stress, and fraught with many sudden arrangements and responsibilities. The last thing a family needs to worry about is being left high and dry, while waiting for a GP to attend the deceased.

Like most people, I strongly believe in dying with dignity — which is why I want to explain the rights you have as an individual or loved one when it comes to GP obligations to the deceased in nursing homes.

Your first call should be to a GP

When a person dies at a nursing home and the death is expected, the first person that should be notified is their GP. The patient’s GP must attend as quickly as possible so that the death certificate (and cremation certificate, if required) can be issued. Only once this has taken place can the deceased be transported to the funeral home. However, given the busy schedules of Australian GPs, it's not always possible for them to attend on the spot. In these cases, nursing home staff may call an after-hours doctor (who may also be limited in availability), or issue a life extinct certificate themselves.

But this is where things get tricky. First and foremost, not all nurses are authorised to issue the life extinct certificate themselves, and, even in the case they are, registered nurses are unable to provide a cremation certificate. Secondly, Medicare provides payment for the death certificate and not the cremation certificate.

Most nursing homes aren’t equipped with mortuary facilities that can hold deceased residents. In desperation, nursing home staff are sometimes forced to call the police to have a body moved. That can be advantageous in the sense that a coroner may issue the death certificate — but it's certainly not the most sensitive way to deal with the peacefully deceased, or the grieving families who are confronted by this scene.

One can only imagine how distressing that experience would be to the families, residents and staff present at the time. Surely resources could be managed more effectively!

The business of medical care

A 2012 AMA report found that over two-thirds of the GPs surveyed had decreased their visits to nursing homes — with the majority attributing this to the non-billable hours and inadequate Government rebates associated with callout visits. But the problem is much broader: last year it was reported that roughly 80% of GPs refuse to offer after-hours visits to the general public at all because of the additional costs incurred by doctors.

That's why most house calls are now handled by private medical deputising services (companies that employ registered medical practitioners to provide after-hours services).

We need to talk about dying

One of the reasons why I became a funeral director was to provide people with genuine, human, support at a time when I knew they needed it most. I don’t feel it’s unreasonable for Australians to expect their GPs provide the same — especially when it comes to aged care, palliative care and dying, from someone who may have serviced the family through all their other medical needs throughout life.

If you are unsure or concerned about the ability for you, a loved one or a patient you care for to access GP services in an aged care facility, don’t be afraid to ask questions. It’s not always the easiest conversation, but it is a critical one. At Lady Anne, we created a Funeral Planning Checklist, which anyone can download, in the hope that it would help people face these difficult discussions head on, and to know the processes and rights of the family of the deceased.

Remember: living and dying with dignity are rights that everyone should have.